System Crasher: 7 Shocking Truths You Must Know Now

Ever wondered what happens when a single person brings down an entire digital ecosystem? Meet the system crasher—a digital saboteur whose actions ripple across networks, companies, and even nations.

What Exactly Is a System Crasher?

The term system crasher might sound like something out of a sci-fi thriller, but it’s very real in today’s hyper-connected world. A system crasher refers to an individual, software, or process that intentionally or unintentionally causes a complete failure in a computing system, network, or application. This can range from crashing a local PC to bringing down massive cloud infrastructures.

Defining the Term: Human vs. Software Crasher

Not all system crashers are created equal. Some are people—hackers, disgruntled employees, or cyber activists—who exploit vulnerabilities. Others are rogue software programs or malware designed to overload systems. For instance, a CISA advisory once highlighted how a single misconfigured script acted as a system crasher across federal networks.

- Human-driven crashers often have malicious intent or ideological motives.

- Software-based crashers may stem from bugs, poor coding, or automated attacks like DDoS.

- Hybrid cases involve both human initiation and automated execution.

Historical Origins of the Term

The phrase ‘system crasher’ gained traction in the 1980s during the rise of personal computing. Early hackers, often called ‘crashers,’ would test system limits by overloading memory or exploiting OS flaws. One infamous case involved the Morris Worm in 1988, which unintentionally became one of the first major system crashers on the internet, infecting thousands of machines.

“The line between curiosity and catastrophe is thin—especially when you’re poking at system boundaries.” — Dr. Linus Tech, Cybersecurity Historian

The Psychology Behind a System Crasher

Understanding why someone becomes a system crasher goes beyond technical skill—it delves into psychology, motivation, and social context. Some act out of rebellion, others for recognition, and a few simply to prove a point about system fragility.

Motivations: Power, Revenge, or Chaos?

Many system crashers are driven by a desire for control. In a world where digital systems govern everything from banking to elections, crashing one can feel like a power move. Revenge is another common motivator—especially among former employees with insider knowledge. Then there are those who crave chaos, finding thrill in disruption without a clear end goal.

- Power seekers aim to demonstrate superiority over complex systems.

- Revenge-driven crashers often target former employers or institutions they feel wronged by.

- Chaos enthusiasts may not care about the outcome—only the act of breaking things.

The Role of Anonymity and Online Culture

The internet provides a mask. A system crasher can operate from a basement in Siberia and take down a server in California without ever revealing their identity. This anonymity fuels risk-taking behavior. Online communities like certain dark web forums or fringe message boards often glorify system crashers as anti-heroes or digital revolutionaries.

Platforms such as 4chan and Reddit have occasionally hosted discussions where users share crash techniques, turning the act into a perverse form of entertainment. While most users don’t act, the normalization of such behavior lowers the barrier for real-world attacks.

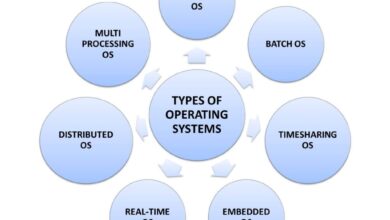

Types of System Crasher Attacks

Not all system crashers use the same methods. The techniques vary widely based on target, tools, and intent. From brute-force overloads to subtle logic bombs, the arsenal of a system crasher is diverse and constantly evolving.

Denial-of-Service (DoS) and DDoS Attacks

One of the most common forms of system crasher activity is the Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack, where a single source overwhelms a system with traffic. When multiple devices are involved—often hijacked through botnets—it becomes a Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attack.

According to Akamai’s State of the Internet Report, DDoS attacks increased by 79% in 2022 alone. These attacks flood servers with requests, exhausting bandwidth or CPU resources until the system collapses.

- Volume-based attacks (e.g., UDP floods) consume bandwidth.

- Protocol attacks (e.g., SYN floods) exploit handshake weaknesses.

- Application-layer attacks (e.g., HTTP floods) mimic real user traffic to exhaust server resources.

Logic Bombs and Time Bombs

A logic bomb is a piece of malicious code that lies dormant until triggered by a specific condition—like a date, user action, or system event. Once activated, it can delete files, corrupt databases, or crash entire systems. The infamous Rajendrasinh Babubhai Makwana case saw a contractor plant a logic bomb in a U.S. company’s network, set to trigger after his contract ended.

Time bombs are a subset of logic bombs, activated by a specific date or time. These are particularly dangerous because they can evade detection for months or even years.

“A logic bomb isn’t just code—it’s betrayal coded in silence.” — Anonymous Security Analyst

Real-World Cases of System Crasher Incidents

The impact of a system crasher isn’t theoretical. History is littered with high-profile cases where individuals or groups caused massive disruptions, sometimes costing millions or endangering lives.

The 2017 NotPetya Cyberattack

Initially disguised as ransomware, NotPetya was later revealed to be a wiper attack designed to destroy data. Believed to be state-sponsored, it began in Ukraine but quickly spread globally, crashing systems at multinational corporations like Maersk, Merck, and FedEx. The total damage exceeded $10 billion.

While not a lone system crasher, the attack was initiated by a compromised software update from a Ukrainian accounting firm. This shows how a single point of failure can turn into a global catastrophe. The incident is studied in cybersecurity circles as a textbook example of cascading system failure.

The GitHub DDoS Attack (2018)

In 2018, GitHub—the world’s largest code hosting platform—was hit by one of the largest DDoS attacks ever recorded. At its peak, the attack generated 1.35 terabits per second of traffic, overwhelming servers and making the site inaccessible for several minutes.

The attackers used a technique called Memcached amplification, exploiting misconfigured servers to magnify their traffic. GitHub restored service within 10 minutes thanks to rapid mitigation, but the event highlighted how even robust platforms can be vulnerable to a determined system crasher.

- Attack lasted approximately 20 minutes.

- Used amplification factor of up to 50,000x.

- Triggered global awareness about UDP-based vulnerabilities.

How System Crashers Exploit Vulnerabilities

No system is 100% secure. System crashers thrive on overlooked flaws, outdated software, and human error. Understanding their methods is key to defending against them.

Zero-Day Exploits and Unpatched Software

A zero-day exploit targets a vulnerability that the vendor doesn’t yet know about—or hasn’t patched. These are gold mines for system crashers. Once discovered, they can be used to gain unauthorized access, escalate privileges, or trigger system crashes.

For example, the SolarWinds breach involved a zero-day in network monitoring software, allowing attackers to insert backdoors into thousands of organizations, including U.S. government agencies.

- Zero-days are often sold on dark web markets for six or seven figures.

- Organizations with slow patch cycles are prime targets.

- Automated scanning tools help crashers find unpatched systems at scale.

Insider Threats: The Silent System Crasher

Not all threats come from outside. Insiders—employees, contractors, or partners—can be the most dangerous system crashers because they already have access, credentials, and knowledge of internal systems.

A 2023 report by Verizon’s DBIR found that 19% of data breaches involved internal actors. Some intentionally sabotage systems, while others accidentally trigger crashes through misconfigurations.

“The most dangerous system crasher isn’t the hacker in a hoodie—it’s the person with admin rights and a grudge.” — Cybersecurity Insider Report, 2023

Preventing System Crasher Attacks

While it’s impossible to eliminate all risks, organizations can significantly reduce their exposure to system crasher threats through proactive defense strategies, employee training, and robust architecture.

Implementing Robust Cybersecurity Frameworks

Frameworks like NIST, ISO 27001, and CIS Controls provide structured approaches to managing cyber risk. These include guidelines for access control, incident response, and system hardening—all critical in stopping a system crasher in their tracks.

For example, the NIST Cybersecurity Framework emphasizes five core functions: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, and Recover. By following these steps, organizations can build resilience against both internal and external crash attempts.

- Regular vulnerability scanning identifies weak points.

- Multi-factor authentication reduces the risk of credential theft.

- Network segmentation limits the blast radius of a crash.

Employee Training and Threat Awareness

Humans are often the weakest link. Phishing emails, social engineering, and poor password hygiene open doors for system crashers. Regular training can turn employees into a first line of defense.

Simulated phishing campaigns, security workshops, and clear reporting protocols help create a culture of vigilance. Companies like Google and Microsoft run mandatory annual security training for all staff, significantly reducing successful breach attempts.

The Future of System Crashers in an AI-Driven World

As artificial intelligence and machine learning become embedded in critical systems, the nature of system crashers is evolving. AI-powered attacks can adapt in real-time, making them harder to detect and stop.

AI-Generated Attacks and Autonomous Crashers

Imagine a system crasher that learns from its failures, modifies its attack strategy, and targets new vulnerabilities without human input. This isn’t science fiction—it’s already happening. AI-driven malware can analyze network behavior, identify optimal attack vectors, and launch precision strikes.

Researchers at Black Hat 2023 demonstrated an AI model that could generate polymorphic viruses capable of evading signature-based detection. These autonomous crashers could one day operate at machine speed, overwhelming traditional defenses.

Quantum Computing and the Next Frontier

Quantum computing promises breakthroughs in medicine, logistics, and cryptography. But it also poses a nightmare scenario for cybersecurity. A quantum-enabled system crasher could break current encryption standards in seconds, rendering SSL, TLS, and blockchain protections obsolete.

While practical quantum attacks are still years away, organizations are already preparing for “Q-day” with post-quantum cryptography. The NIST Post-Quantum Cryptography Project is standardizing new algorithms to resist quantum decryption, a critical step in future-proofing against next-gen system crashers.

Legal and Ethical Implications of Being a System Crasher

Crashing a system isn’t just technically risky—it’s legally dangerous. Laws around the world criminalize unauthorized access, data destruction, and network disruption, with penalties ranging from fines to decades in prison.

Global Cybercrime Laws and Prosecution

In the U.S., the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) is the primary tool for prosecuting system crashers. Violations can lead to up to 10 years in prison for first offenses and 20+ years for repeat or damaging attacks.

Internationally, the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime sets a legal framework for cooperation between nations. Countries like the UK, Germany, and Japan have their own stringent laws, making cross-border prosecution more feasible.

- The CFAA has been criticized for being overly broad.

- Some activists argue that ethical hacking should be protected.

- Whistleblowers like Edward Snowden walk a fine line between hero and system crasher in the eyes of the law.

Gray Areas: Hacktivism vs. Malicious Crashing

Where do we draw the line between protest and crime? Groups like Anonymous have launched DDoS attacks on government and corporate sites to protest censorship, surveillance, or corruption. While they claim moral justification, their actions still constitute illegal system crashing.

This raises ethical questions: Can digital civil disobedience ever be justified? Should intent matter in sentencing? These debates continue in legal and academic circles, with no clear consensus.

“When code becomes protest, the law struggles to keep up.” — Legal Tech Journal, 2022

What is a system crasher?

A system crasher is an individual, software, or process that causes a computing system to fail, either intentionally through malicious attacks or unintentionally via bugs and misconfigurations.

How do system crashers typically attack?

Common methods include DDoS attacks, logic bombs, zero-day exploits, and insider threats. They exploit vulnerabilities in software, networks, or human behavior to trigger system failures.

Can a system crasher be stopped?

Yes, through robust cybersecurity practices like regular patching, employee training, intrusion detection systems, and adherence to security frameworks like NIST or ISO 27001.

Are all system crashers hackers?

Not necessarily. While many are skilled hackers, some system crashers are ordinary users who accidentally trigger crashes through misconfiguration, while others use automated tools without deep technical knowledge.

What’s the difference between a virus and a system crasher?

A virus is a type of malware that replicates itself, while a system crasher is any entity (person, code, or process) that causes system failure. A virus can be a tool used by a system crasher, but not all crashers use viruses.

From lone hackers to AI-powered threats, the phenomenon of the system crasher continues to evolve. These digital disruptors exploit weaknesses in technology, psychology, and law, challenging our notions of security and control. While their methods grow more sophisticated, so too do our defenses. By understanding the motivations, techniques, and consequences of system crashers, organizations and individuals can better prepare for the inevitable attempts to break the system. The digital world will always have vulnerabilities—but with vigilance, education, and innovation, we can minimize the damage and keep our systems running.

Further Reading: