System Failure: 7 Shocking Causes and How to Prevent Them

Ever wondered what happens when everything suddenly stops working? From power grids to software networks, a system failure can bring life to a standstill in seconds. Let’s dive into the real stories behind these breakdowns and how we can avoid them.

Understanding System Failure: What It Really Means

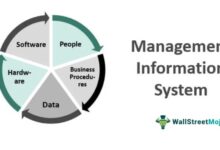

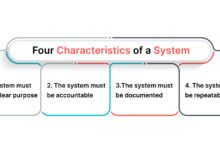

A system failure occurs when a network, machine, process, or organization fails to perform its intended function, leading to disruptions, losses, or even disasters. While it sounds technical, system failure isn’t limited to computers or engineering—it spans healthcare, transportation, finance, and even social structures.

Defining System Failure in Modern Context

In today’s interconnected world, a system is any organized set of components working together toward a common goal. When one or more components malfunction or interact poorly, the entire system can collapse. According to NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology), system failure often stems from design flaws, human error, or external stressors.

- A system can be mechanical, digital, biological, or organizational.

- Failure doesn’t always mean total shutdown—it can be partial degradation.

- The impact varies from minor inconvenience to catastrophic loss.

“A system is only as strong as its weakest link.” — Often attributed to systems theorist Ludwig von Bertalanffy

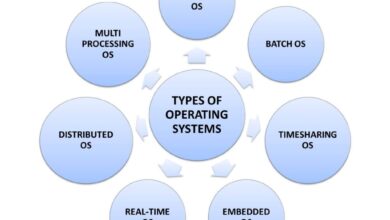

Types of System Failures

Not all system failures are created equal. They can be categorized based on origin, scope, and duration:

- Hardware Failure: Physical components like servers, engines, or circuits break down.

- Software Failure: Bugs, crashes, or incompatibilities in code cause malfunctions.

- Human-Induced Failure: Errors in operation, maintenance, or decision-making trigger collapse.

- Environmental Failure: Natural disasters, power outages, or cyberattacks disrupt operations.

- Cascading Failure: One failure triggers a chain reaction across interdependent systems.

Understanding these types helps organizations prepare better contingency plans and improve resilience.

Historical Examples of Major System Failures

History is littered with system failures that reshaped industries, regulations, and public trust. These cases serve as cautionary tales and learning opportunities for engineers, policymakers, and business leaders alike.

The 2003 Northeast Blackout

On August 14, 2003, a massive power outage affected over 50 million people across the northeastern United States and parts of Canada. The root cause? A software bug in an alarm system at FirstEnergy Corporation’s control room.

The system failure began when overloaded transmission lines sagged into trees due to inadequate maintenance. The energy management system failed to alert operators because of a flawed software module. Without timely warnings, the grid became unstable, leading to a cascading blackout that lasted up to two days in some areas.

This incident cost an estimated $6 billion and led to sweeping reforms in grid monitoring standards. The U.S.-Canada Power System Outage Task Force later recommended mandatory reliability standards enforced by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Therac-25 Radiation Therapy Machine Disaster

In the mid-1980s, the Therac-25, a medical linear accelerator used for cancer treatment, caused at least six known accidents where patients received massive radiation overdoses—some hundreds of times higher than intended. Several patients died or suffered severe injuries.

The root cause was a software race condition: two operators could input commands so quickly that the system failed to validate safety checks. Engineers had reused code from older models without proper testing for the new configuration. The system failure was not due to hardware malfunction but to poor software design and lack of independent review.

“The Therac-25 accidents are among the most studied cases in software engineering ethics.” — Nancy Leveson, MIT Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics

This tragedy revolutionized medical device regulation and emphasized the need for fail-safe mechanisms and rigorous software validation.

The Challenger Space Shuttle Disaster

Common Causes Behind System Failure

While every system failure has unique circumstances, research shows recurring patterns in their origins. Identifying these common causes is crucial for prevention and risk mitigation across industries.

Poor Design and Engineering Flaws

One of the most fundamental causes of system failure is flawed design. This includes inadequate stress testing, poor material selection, or failure to account for real-world operating conditions.

For example, the collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940—nicknamed “Galloping Gertie”—was caused by an aerodynamically unstable design that made it susceptible to wind-induced oscillations. Engineers had not anticipated how airflow would interact with the bridge’s narrow deck.

In digital systems, poor architecture can lead to bottlenecks, memory leaks, or single points of failure. A well-known case is the 2021 Facebook outage, where a configuration change in the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) caused all of Facebook’s IP addresses to vanish from the internet. The design lacked sufficient redundancy and automated rollback mechanisms.

- Design must include edge-case analysis and stress simulations.

- Peer reviews and third-party audits reduce oversight risks.

- Modular design allows isolation of failures.

Human Error and Organizational Blind Spots

Despite advances in automation, humans remain central to system operation and maintenance. Human error contributes to over 70% of industrial accidents, according to the UK Health and Safety Executive.

Errors can include miscommunication, fatigue, inadequate training, or overconfidence in automated systems. In the 1979 Three Mile Island nuclear accident, operators misread a valve status indicator and shut down emergency cooling, worsening the partial meltdown.

Organizational culture also plays a role. In NASA’s Columbia disaster (2003), engineers had raised concerns about foam strike damage during launch, but management dismissed them due to normalization of deviance—a culture where recurring anomalies are accepted as normal.

“It’s not the error that causes the failure, it’s the system’s inability to detect and correct it.” — Sidney Dekker, safety expert

Software Bugs and Cyber Vulnerabilities

In the digital age, software underpins nearly every critical system. A single line of faulty code can trigger widespread disruption.

The 2017 British Airways IT meltdown, which stranded 75,000 passengers, was caused by an engineer disconnecting a power supply without following proper procedures. But the deeper issue was the lack of redundancy and monitoring in their data center. The system failure cascaded through reservation, check-in, and boarding systems.

Cyberattacks are another growing threat. The 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack forced a shutdown of fuel supply across the U.S. East Coast. Hackers exploited a single compromised password to gain access, highlighting weak cybersecurity hygiene.

- Regular penetration testing is essential.

- Zero-trust security models reduce attack surfaces.

- Automated monitoring can detect anomalies early.

How System Failure Impacts Different Industries

The consequences of system failure vary dramatically depending on the sector. What might be a minor glitch in one industry can be life-threatening in another. Let’s explore how different fields experience and respond to breakdowns.

Healthcare: When Lives Hang in the Balance

In healthcare, system failure can mean the difference between life and death. Electronic health records (EHR) going offline, misconfigured medical devices, or communication breakdowns during emergencies can have fatal outcomes.

A 2020 report by the National Institutes of Health found that EHR downtime events led to delayed treatments, medication errors, and increased mortality in intensive care units.

Hospitals now implement disaster recovery plans, including paper backups and offline protocols, to maintain operations during IT outages. However, training and coordination remain inconsistent across institutions.

Aviation: Precision Under Pressure

The aviation industry operates under some of the strictest safety standards globally. Yet, system failures still occur—often due to sensor malfunctions, software errors, or pilot-system miscommunication.

The Boeing 737 MAX crashes in 2018 and 2019, which killed 346 people, were linked to the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). The system relied on a single angle-of-attack sensor. When it failed, MCAS repeatedly forced the plane’s nose down, overriding pilot inputs.

This system failure exposed flaws in certification processes, pilot training, and corporate transparency. Boeing later redesigned MCAS with dual-sensor input and improved pilot alerts.

“Automation should assist pilots, not replace their judgment.” — International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

Financial Systems: The Cost of Downtime

In finance, system failure can trigger market volatility, lost transactions, and erosion of public trust. Stock exchanges, payment processors, and banks rely on high-frequency, low-latency systems that must operate 24/7.

In 2012, Knight Capital lost $440 million in 45 minutes due to a software deployment error. A legacy code module was accidentally activated, causing the firm’s algorithms to buy high and sell low uncontrollably.

Regulators like the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) now require firms to implement circuit breakers, kill switches, and pre-deployment testing protocols to prevent similar disasters.

The Role of Redundancy in Preventing System Failure

One of the most effective strategies for mitigating system failure is redundancy—the practice of building backup components or pathways that take over when primary systems fail.

What Is Redundancy and Why It Matters

Redundancy ensures that no single point of failure can bring down an entire system. It’s a core principle in engineering, IT, aerospace, and emergency response planning.

For example, data centers use redundant power supplies, cooling systems, and network connections. If one server fails, others instantly pick up the load. Similarly, aircraft have multiple hydraulic systems and flight control computers.

However, redundancy alone isn’t enough. If backup systems share the same design flaws or are managed by the same flawed process, they can fail simultaneously. This is known as common-cause failure.

- Redundancy must be diverse (different designs, vendors, or locations).

- Failover mechanisms should be automatic and tested regularly.

- Monitoring tools must detect primary failures quickly.

Case Study: The Mars Rover’s Fault Protection

NASA’s Mars rovers, like Curiosity and Perseverance, operate millions of miles from Earth with no possibility of physical repair. Their survival depends on robust fault protection systems.

These rovers use redundant computers, sensors, and communication channels. If the primary computer crashes, the backup automatically boots up. Software includes self-diagnostic routines that can suspend non-critical operations and enter safe mode.

During the 2018 global dust storm on Mars, Opportunity’s solar panels were covered, leading to power loss. While the rover didn’t survive, its system failure was due to environmental limits, not design flaws. Future missions now include nuclear power sources (RTGs) to avoid similar issues.

“Redundancy is not about preventing failure—it’s about surviving it.” — NASA Systems Engineering Handbook

Early Warning Signs of Impending System Failure

Most system failures don’t happen without warning. Subtle indicators—often ignored or misunderstood—can signal deeper problems brewing beneath the surface.

Performance Degradation and Latency Spikes

One of the earliest signs of system failure is a gradual decline in performance. Users may experience slow response times, timeouts, or intermittent errors.

In IT systems, latency spikes can indicate network congestion, memory leaks, or disk I/O bottlenecks. Monitoring tools like Prometheus, Grafana, or New Relic help visualize these trends before they escalate.

For example, before the 2015 Amazon Web Services (AWS) S3 outage, users reported increased error rates and slow access. The issue stemmed from a configuration error in the US-East-1 region, which cascaded due to high inter-service dependencies.

Increased Error Rates and Log Anomalies

System logs are treasure troves of diagnostic information. A sudden spike in error messages—especially critical or fatal errors—should trigger immediate investigation.

Machine learning tools can now analyze log patterns to predict failures before they occur. Google’s SRE (Site Reliability Engineering) team uses anomaly detection algorithms to identify deviations from normal behavior.

Ignoring log warnings can be costly. In the 2016 TSB banking migration fiasco, thousands of customers couldn’t access their accounts for weeks. Post-mortem analysis revealed that error logs had shown severe issues during testing, but were dismissed as “expected during migration.”

User Complaints and Feedback Loops

End-users are often the first to notice problems. A surge in support tickets, social media complaints, or negative reviews can be early indicators of system failure.

Organizations must establish feedback loops that escalate user-reported issues to engineering and operations teams. Southwest Airlines’ 2022 holiday meltdown, which canceled over 16,000 flights, was preceded by pilot and crew complaints about outdated scheduling software.

- Implement real-time user feedback dashboards.

- Train support staff to recognize and report systemic issues.

- Conduct root cause analysis after every major incident.

Strategies to Prevent and Recover from System Failure

Preventing system failure requires a proactive, multi-layered approach. It’s not just about fixing problems—it’s about building resilient systems that can adapt and recover.

Implementing Robust Testing and Simulation

No system should go live without rigorous testing. This includes unit testing, integration testing, load testing, and disaster recovery drills.

Chaos Engineering, pioneered by Netflix with its Chaos Monkey tool, deliberately injects failures into systems to test resilience. By randomly shutting down servers or simulating network delays, engineers learn how systems behave under stress.

Organizations like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft run regular “game days” where teams simulate outages and practice response protocols. These exercises uncover hidden dependencies and improve coordination.

“You don’t rise to the level of your goals, you fall to the level of your training.” — Archilochos (adapted for system resilience)

Adopting a Culture of Blameless Post-Mortems

When a system failure occurs, the focus should be on learning, not punishment. Blameless post-mortems encourage transparency and continuous improvement.

At Etsy and GitHub, post-mortem reports are public and include: what happened, why it happened, how it was fixed, and what will be done to prevent recurrence. The goal is to identify systemic issues, not individual mistakes.

This culture reduces fear of reporting errors and fosters collaboration. According to Google’s SRE book, “The root cause of almost every outage is a recent change.” Tracking and reviewing changes is critical.

Building Resilient Architectures with Microservices

Modern systems are shifting from monolithic designs to microservices—small, independent components that communicate via APIs. This architecture limits the blast radius of failures.

For example, if a recommendation engine fails in an e-commerce app, users can still browse and purchase items. In a monolithic system, one crash could take down the entire platform.

However, microservices introduce complexity in monitoring and data consistency. Tools like Kubernetes, Istio, and service meshes help manage this complexity and ensure reliability.

Future Trends: AI, Automation, and System Resilience

As artificial intelligence and automation become integral to critical systems, the nature of system failure is evolving. New opportunities for resilience emerge, but so do new risks.

AI-Powered Predictive Maintenance

AI is transforming how we predict and prevent system failure. Machine learning models can analyze sensor data from industrial equipment to forecast when a machine is likely to fail.

General Electric uses AI to monitor jet engines in real time, predicting maintenance needs before breakdowns occur. This reduces unplanned downtime and extends equipment life.

In IT, AI-driven observability platforms like Datadog and Splunk use anomaly detection to flag unusual behavior, enabling faster response times.

The Risks of Over-Automation

While automation improves efficiency, over-reliance can be dangerous. When humans are removed from the loop, they lose situational awareness and may be unprepared to intervene during a crisis.

The 2009 Air France Flight 447 crash was partly attributed to pilots’ confusion when autopilot disengaged due to sensor icing. They failed to recognize a stall and made incorrect control inputs.

Future systems must balance automation with human oversight. Adaptive automation—where control shifts based on context—may offer a safer path forward.

Quantum Computing and System Security

Quantum computing promises unprecedented processing power but also threatens current encryption methods. A quantum-enabled cyberattack could break RSA encryption, leading to massive system failures in banking, defense, and communications.

Organizations are already researching post-quantum cryptography to future-proof their systems. The NIST is leading a global effort to standardize quantum-resistant algorithms.

Preparing for this shift is critical to avoid a systemic security collapse when quantum computers become mainstream.

What is a system failure?

A system failure occurs when a network, machine, or process stops functioning as intended, leading to disruption or collapse. It can be caused by hardware defects, software bugs, human error, or external events like natural disasters.

What are the most common causes of system failure?

The most common causes include poor design, human error, software bugs, lack of redundancy, and cyberattacks. Often, a combination of factors leads to catastrophic breakdowns.

How can organizations prevent system failure?

Organizations can prevent system failure by implementing redundancy, conducting regular testing, fostering a blameless culture, using predictive analytics, and designing resilient architectures like microservices.

Can AI prevent system failure?

Yes, AI can help predict and prevent system failure through anomaly detection, predictive maintenance, and real-time monitoring. However, over-reliance on AI without human oversight can introduce new risks.

What should you do during a system failure?

During a system failure, activate emergency protocols, communicate clearly with stakeholders, isolate the affected components, and follow a documented incident response plan. Afterward, conduct a post-mortem to prevent recurrence.

System failure is an inevitable risk in any complex system, but it doesn’t have to be a disaster. By understanding its causes—from flawed design to human error—and implementing strategies like redundancy, predictive monitoring, and blameless post-mortems, organizations can build resilience. The future of system reliability lies in balancing automation with human judgment, embracing transparency, and learning from past mistakes. As technology evolves, so must our approach to safeguarding the systems we depend on every day.

Further Reading: